The Indus Dictionary Project

info@indusproject.org

www.indusproject.org

Liji - Pictographs and Foreign Affairs

Lǐjì 禮記, the Record of Rites, is a Chinese book of descriptions of ancient customs, rituals, and regulations. It is around 2,500 years old, and is held to be a compilation of much older texts.

One of the texts, the Wángzhì 王制 deals with royal systems or procedures. This includes a paragraph (number 36), which is concerned with the five directions, in other words foreign affairs.

In my opinion, the last sentence of Wángzhì, paragraph 36 resembles the kind of aide memoire that is associated with oral history. It may appear to be a simple list, but it contains layers of information and meaning.

My interpretation of the aide memoire, is that Liji first tells us that pictographs were very important as a tool for foreign affairs, because their meaning was obvious. It then goes on to explain that they could be used for dealing with foreign bureaucracy, and that it was possible to communicate with people face to face, or at a distance.

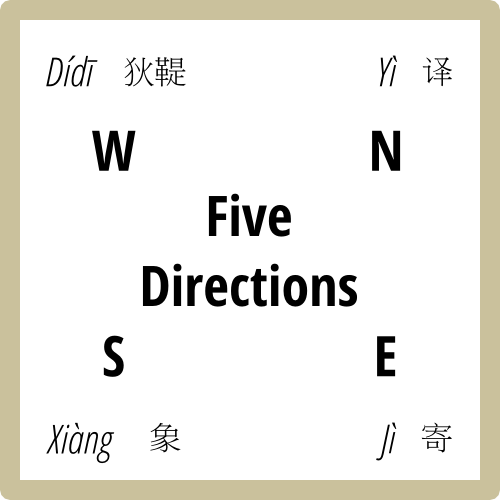

To illustrate my interpretation of the aide memoire, I have prepared the diagram below.

Please note that my interpretation differs from both the Legge (English)¹ and the Couvreur (French)² translations of the last sentence of paragraph 36.

The last sentence of paragraph 36 refers to each of the cardinal points. The cardinal points are positioned in the diagram according to the Bronze Age convention for maps.

- The Five Directions or Foreign Affairs: The idea is that you are in the centre with the four cardinal points around you.

Wángzhì, paragraph 36 uses the cardinal directions as bullet points:

- South: The South is the most important direction, because it gets the midday sun, in other words, the best possible light.

- Xiàng 象: Pictographs: The Chinese character is an elephant, but I would argue that it represents a mammoth. It is something very large, presented here, in the best possible light. It follows that it cannot be missed.

- West: This is the direction towards which the sun sets. When the sun sets, activity is limited by the absence of good light. At this time, people's thoughts turn to leisure.

- Dídī 狄鞮: A Foreigner in Leather Shoes: This is someone who has a fairly leisured or easy existence. It can be translated as a foreign official.

- North: The direction north has the worst possible light, when literally or figuratively, you might be in the dark.

- Yì 译: The Verb: to Translate: Even today, in China, if you are speaking to someone, and say that you don't understand, they may respond by writing down the characters for what they have just said. That is what Liji is referring to here: the ability to use pictographs to communicate when two or more people do not share a common spoken language.

- East: This is the direction from which the sun rises.

- Jì 寄: The Verb: to Send a Message: A long distance messenger would be sent out at dawn.

References:

1. James Legge, 1885: Sacred Books of the East: Volume 27: Oxford University Press: http://ctext.org/liji: Accessed: 30 September 2016.

2. Séraphin Couvreur, 1913: Li Ki, ou Mémoires sur les bienséances; texte Chinois avec une double traduction en Francais et en Latin: Second Edition: Volume 1: Hokkien: Mission Catholique: https://archive.org/details/likioummoiress01couvuoft: Accessed: 30 September 2016.